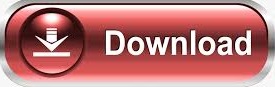

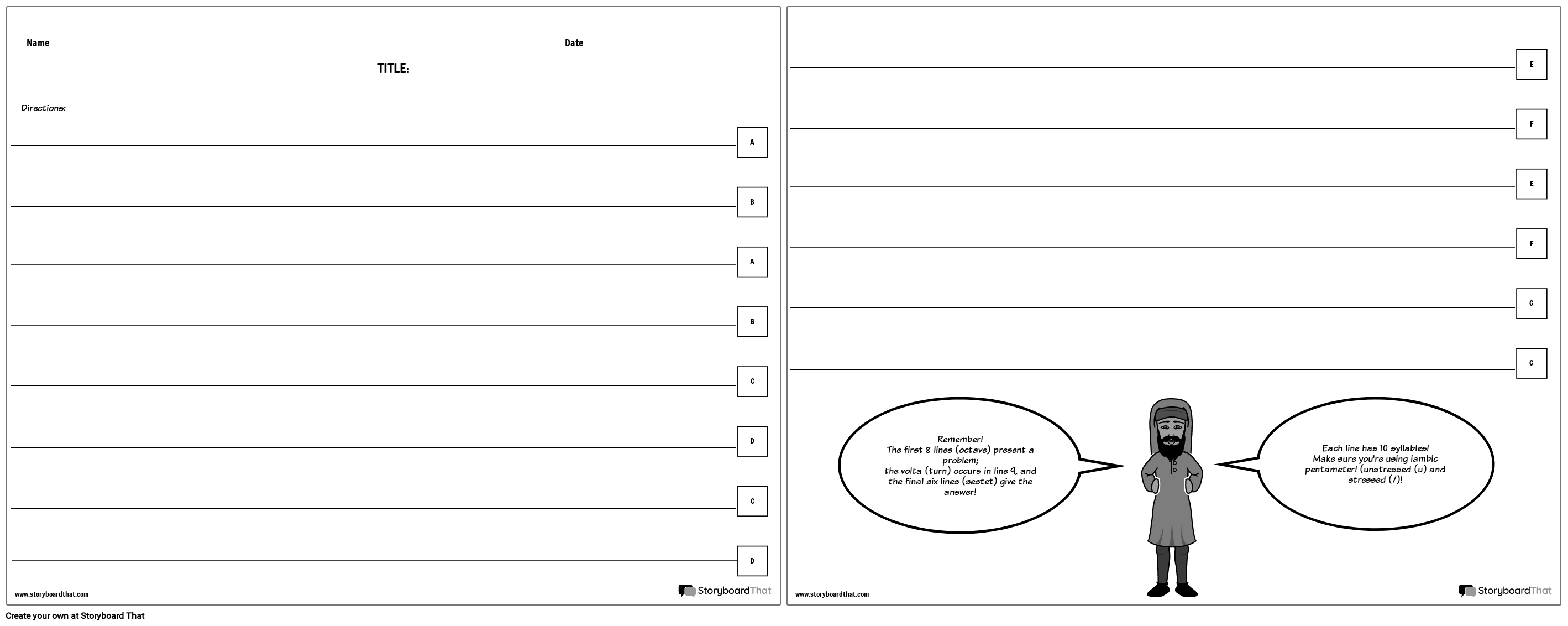

The point here is that the poem is divided into two sections bythe two differing rhyme groups. In strict practice, the one thing that is to be avoidedin the sestet is ending with a couplet (dd or ee), as this wasnever permitted in Italy, and Petrarch himself (supposedly) never used a couplet ending in actual practice, sestets aresometimes ended with couplets (Sidney's "Sonnet LXXI givenbelow is an example of such a terminal couplet in an Italiansonnet). The exact pattern of sestet rhymes (unlike the octave pattern)is flexible. The remaining 6 lines is called the sestet and can haveeither two or three rhyming sounds, arranged in a variety ofways: c d c d c d The first 8 lines is called the octaveand rhymes: a b b a a b b a The Italian sonnet is divided into two sections by two differentgroups of rhyming sounds. The basic meter of all sonnets in English is iambic pentameter ( basic information on iambic pentameter),although there have been a few tetrameter and even hexametersonnets, as well. There are, of course, other types of sonnets,as well, but I'll stick for now to just the basic three (Italian, Spenserian, English), with a brief look at some non-standard sonnets.

Each of the three major types of sonnets accomplishesthis in a somewhat different way. Basically, in a sonnet, youshow two related but differing things to the reader in order to communicatesomething about them. I’ll listen to your words- you know I’m fair.Basic Sonnet Forms Basic Sonnet Forms Nelson Miller From the Cayuse Press Writers Exchange BoardĪ sonnet is fundamentally a dialectical construct which allows the poet to examine the nature and ramifications of two usually contrastive ideas,emotions, states of mind, beliefs, actions, events, images, etc., byjuxtaposing the two against each other, and possibly resolving or justrevealing the tensions created and operative between the two. My love, use whispers closely late tonight. There’s nothing risked delaying words that grate. So hold those words for later don’t despair The thoughts that form those words might disappear.

They’re best unsaid than trying to attone. We’ve both before said words we can’t disown, Harsh words once thrown will travel like a spear. You’ll want to be assured your meaning’s clear. I ask that first you test your words alone. Should you be moved to speak in anger, dear, Tell Me of Your Anger in Whispers (Italian Sonnet) Whatever the changes made by poets exercising artistic license, no “proper” Italian sonnet has more than five different rhymes in it. These poets do not necessarily restrict themselves to the strict metrical or rhyme schemes of the traditional Petrarchan form some use iambic hexameter, while others do not observe the octave-sestet division created by the traditional rhyme scheme.

Poets adopting the Petrarchan sonnet form often adapt the form to their own ends to create various effects. The first known sonnets in English, written by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, used this Italian scheme, as did sonnets by later English poets including John Milton, Thomas Gray, William Wordsworth and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. In time, other variants on this rhyming scheme were introduced such as c-d-c-d-c-d. For the sestet there were two different possibilities, c-d-e-c-d-e and c-d-c-c-d-c. In the sonnets of Giacomo da Lentini, the octave rhymed a-b-a-b, a-b-a-b later, the a-b-b-a, a-b-b-a pattern became the standard for Italian sonnets. Even in sonnets that don’t strictly follow the problem/resolution structure, the ninth line still often marks a volta by signaling a change in the tone, mood, or stance of the poem. Typically, the ninth line creates a “turn” or volta, which signals the move from proposition to resolution. First, the octave (two quatrains, or two groups of four lines), which describe a problem, followed by a sestet (two tercets, two groups of three lines), which gives the resolution to it. 1250–1300) wrote sonnets, but the most famous early sonneteer was Petrarca (known in English as Petrarch). Other Italian poets of the time, including Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) and Guido Cavalcanti (c. Guittone d’Arezzo rediscovered it and brought it to Tuscany where he adapted it to his language when he founded the Neo-Sicilian School (1235–1294). The Italian sonnet was created by Giacomo da Lentini, head of the Sicilian School under Frederick II. Usually, English and Italian Sonnets have 10 syllables per line, but Italian Sonnets can also have 11 syllables per line. An Italian sonnet is composed of an octave, rhyming abbaabba, and a sestet, rhyming cdecde or cdcdcd, or in some variant pattern, but with no closing couplet.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)